In 2013, 24.4 million hectares of GM crops were grown in Argentina – mostly soy, maize and cotton.

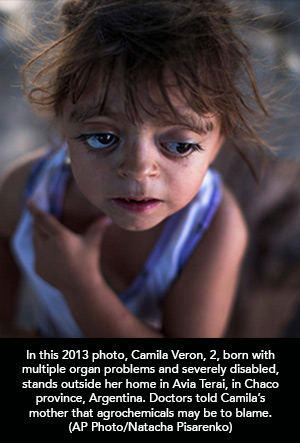

The public health consequences of GMO cultivation in Argentina have been extensively publicised, with cancer and birth defects skyrocketing in areas where GM crops are sprayed with Roundup herbicide.

GMWatch and Earth Open Source (which published the “Roundup and birth defects” report) initially raised these issues with UK and European politicians and retailers back in 2010. They met with the response that these were internal issues for the Argentine government and nothing to do with them. Some said that if things really were that bad, the Argentine government would “not allow” it to go on and regulators would step in and ban the cultivation of GMOs.

So why does the Argentine government allow it to go on? Apart from the fact, that is, that the Argentine government receives 35% in taxes on GMO soy exports?

The answer, as the Argentine journalist Dario Aranda explains in the exposé below, may be that the Argentine GMO regulator Conabia is stacked with people who have conflicts of interest with the GMO industry.

People with links to Monsanto, Syngenta and Dow evaluate the safety of the GMOs submitted for approval by these exact same companies.

This GMO company-regulatory nexus affects us all because the resulting GMOs end up in our food and livestock feed.

In a particularly dangerous development, as Aranda notes, Conabia has been selected as a “reference centre” for the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO). In this role Conabia will “provide technical and scientific advice” to the FAO regarding the “biosafety” of GMOs. So now we have people linked to the leading GMO developer companies, Monsanto, Syngenta, and Dow, telling the world’s major food security organisation whether GMOs are safe. Perfect!

—

Who approves GMOs in Argentina? A business run by its owners

A key organisation in the authorization of GMOs in Argentina is dominated by agribusiness and scientists with links to the private sector. Monsanto, Syngenta, Ledesma and Dow, among other corporations, are found on both sides of the table, in a story of conflicts of interest and a complicit state. Dario Aranda* reports

The multinationals Monsanto, Bayer, Syngenta and Dow are a few of the companies that have a say in the approval of the GMOs that are driven by those same companies. We are talking about Conabia (Comisión Nacional Asesora de Biotecnología Agropecuaria, National Agricultural Biotechnology Advisory Committee), where “national” businesses (Biosidus and Don Mario) and business organisations also participate.

“Independent researchers” are also a part of Conabia, but they have clear links to the companies. The government and companies publicize Conabia as “apioneering forum with a solid and scientifically based regulatory framework”. Out of the 47 members, more than half (27) are employed by [pertenecen = belong to] the companies or have a clear link with the same companies that they must regulate.

Conflicts of interest and complicities are present in the approval of GMOs in Argentina.

Conabia

The Comisión Nacional Asesora de Biotecnología Agropecuaria (Conabia) (National Advisory Comission on Agricultural Biotehnology), founded in 1991, works under the Agricultural Ministry and acts in tandem with the Dirección de Biotecnología (Directorate of Biotechnology), also working under the Ministry. Its main goal is to “guarantee the agroecosystem’s biosafety”.

According to official information, Conabia “analyzes and assesses the applications submitted in order to develop activities involving GMOs (genetically modified organisms – transgenics). Based on scientific and technical information and quantitative data regarding the biosafety of the GMO, it issues a ruling for the release or rejection of the corporate request.

Conabia acknowledges that it comprises representatives of both the public and private sector and calls them “experts”. Conabia clarifies on its website that “members must declare any kind of conflict of interest that might surface during the assessment of the applications presented. This is essential in order to guarantee the transparency of such rulings”.